The Northern Arapaho People Who Made Me

My Wind River co-workers, counselors, supporters, prayer warriors and friends

Preface: “If your path is too smooth, you’re on the wrong path.”

Several lifetimes ago, before I earned my federal Bureau of Prisons letter jacket for providing cannabis free of charge to dying AIDS and cancer patients in Tennessee, before I became a “Jolly Blue Giant” raising the best organic blueberries and blackberries to feed middle Tennessee families and give them memory-making moments on my berry ridge; before all that, I was a public health epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control developing AIDS-related research protocols for an epidemic that I had spent four years fighting, a fight that had almost worn me out when we still had no adequate treatment response to the virus.

The New Mexico Department of Health came to my rescue, hiring me to move to Santa Fe and develop the first research unit within any state department of health anywhere to study substance abuse as a public health problem, applying the same epidemiological research principles that we use to track infectious disease. The two years I was there (in 1991-92) were among the most creative, productive and far reaching of my career and led me to be appointed a Congressional advisor on substance abuse in the Bush 1 and Clinton administrations. It also resulted in the federal government deciding to fund all states to replicate our research protocols to help inform their own decisions regarding support for substance abuse prevention and treatment services. I helped a number of states develop their research proposals and in 1996, I wrote the proposal for Wyoming that was awarded the single largest contract by the feds to ANY state in that competition, almost $1.5 million, even though Wyoming is the least populated state in the country.

That award meant that I would spend much of the next five years in the Equality State, Wyoming’s other name besides the Cowboy State since they were the first to give women the right to vote. I was to be directly responsible for four of the eleven studies, to oversee the others conducted primarily by University of Wyoming researchers and then to write the final reports that resulted in informing and mobilizing the Wyoming citizenry to demand attention to their serious substance abuse problems. As a result, the Wyoming legislature increased state funding for substance abuse prevention and treatment services by over 600%. From an epidemiological perspective and from the perspective of a person (me) in recovery, those were definitely good times.

One of the studies I was directly responsible for was to assess the incidence and prevalence of substance abuse among American Indian populations in the state. Most of those Indian people were Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone, long standing enemies who had been forced in the 1880s by the US cavalry to inhabit the same reservation in central Wyoming (the Wind River Reservation) “until the next spring came” when the Northern Arapaho were to be moved elsewhere. As an Eastern Shoshone leader told me soon after arriving in Wind River Country, spring had still not arrived there over a century later.

What that work brought me was so much more than I could have imagined. It brought me into close contact with the Northern Arapaho people with whom I was to develop a deep, abiding and long-lasting trust and mutual respect, the rewards for which continue to bless me today. It also brought me into a friendship with four Northern Arapaho leaders in particular and into the prayers of the entire Tribe when I needed them most. Let me introduce you to those friends, all of whom are hunting happily now in the afterlife.

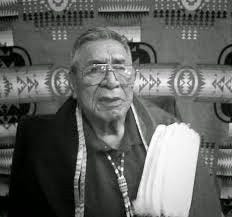

Paul Joe Hanway “If we wonder often, the gift of knowledge will come.”

Shortly after I began working for Wyoming collecting local, statewide and Tribal data from relevant agencies to document the alarmingly high levels of substance abuse there, I gave a presentation to the Fremont County Commission, five White cowboys who led the county in which the Wind River Reservation was located. Before my presentation, I invited the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone leaders to join us. It was a pretty gloomy half hour presenting statistics that everyone in the room knew better than me because they lived their consequences every day. For example, even though Indian people made up only 2% of Wyoming’s population, they accounted for 16% of the state’s alcohol-involved deaths. The county’s alcohol-related traffic crash and arrest rates far exceeded the state and national rates for these serious problems. On and on, chart after chart, I kept going, noticing that my audience kept sinking lower in their seats, their resigned looks becoming more painfully obvious.

Fortunately, I decided to end my presentation by sharing data from a similar study I was conducting in McKinley County, New Mexico whose county seat Gallup (nicknamed “Drunk Town”) was undergoing a seismic transformation to address their substance abuse problems. Their efforts had already resulted in dropping McKinley County’s alcohol-involved mortality rate from the WORST in the entire country to a rate lower than half of all other New Mexico counties. Their alcohol-related arrest rate had dropped 95% and their alcohol-related traffic crash rate, once more than three times the state rate, was now below the state rate and continuing to drop.

With each new “Drunk Town” slide, the Fremont and Wind River audience got more alert and attentive. When I finished, the Chairman of the County Commission asked me one question: ”How do we get to Gallup?” He was immediately followed by Paul Joe Hanway, the Northern Arapaho Tribal Health Director, who asked “How soon can we get to Gallup?” At that moment, my role shifted from simply being a substance abuse epidemiologist to becoming a community organizer and facilitator between these two Indian Country communities. Beginning with the first group of Wind River Country leaders who I arranged to visit Gallup, I organized four more site visits that took a total of forty five Fremont/Wind River Country leaders to Gallup. During that time, I also organized two groups of Gallup leaders to visit Wind River Country.

From the beginning, Paul Joe made sure that the Northern Arapaho were represented every time these site visits occurred. During the first visit to Gallup, Paul Joe and other Northern Arapaho leaders held an impromptu meeting with the Navajo, Zuni, Acoma and Laguna leaders who were involved in Gallup’s transformation. At that meeting, Paul Joe didn’t mince words, asking a Navajo leader: “So what’s the story with this Ellis guy? Can we trust him?” That Navajo leader’s response was equally brief: “Not only can you trust Bernie but if you support him as he does his (substance abuse epidemiology) thing, the rewards to your people and everyone else in Wind River Country will be beyond your wildest imaginings.” That’s all Paul Joe and the other Northern Arapaho leaders needed to hear. From that day forward, they opened every door that needed to be opened for me, with smiles on their faces.

Paul Joe and I began regular weekly visits to map out what his people needed to reduce substance abuse. We identified the pressing need for a detox center in Wind River Country patterned on the Na’nizhoozhi Center in Gallup, the largest treatment center anywhere in the country. We also discussed the need for treatment and referral services for county jail inmates, almost 80% of whom were locked up for some substance abuse-related crime. And we envisioned introducing Native spirituality and support into everything we pursued. The needs we mapped out morphed into a marathon grant writing spree on my part as well as my helping support a local tax initiative to build a new jail that would provide in-house substance abuse treatment and linkage to Tribal support services when, heretofore, the Tribes and the Fremont County Sheriff had always kept their distance. Over the next two years, we obtained over $17 million in federal and state grant funds and a local tax referendum to fund the new jail that passed by a 13% margin of victory in a very anti-tax state.

The day after the tax initiative passed, Paul Joe invited me to the opening of a new Veterans Affairs health clinic on the rez. We were both beaming from the successful referendum vote and after the dedication of the new facility, Paul Joe motioned me over to meet the regional VA director. Paul Joe’s introduction was short and puzzling. Turning to the VA director, he said “I’d like you to meet Bernie Ellis. He has been of great service to our people and he can kick your ass”. Neither the VA official nor I knew where to go from there so I timidly shook his hand and went back to my office. Later that day, I recounted that introduction to another Northern Arapaho leader and said I didn’t know what to make of it. The leader smiled at me and said, “Bernie, it’s pretty simple. Paul Joe was paying you the highest compliment we have. He was identifying you as a warrior for our people.”

Burton Hutchinson “Take only what you need and leave the land as you found it.”

Burton Hutchinson was one of the stateliest and most soft spoken elders on the Northern Arapaho Tribal Council, a towering and gentle man revered by all his people. One of the first times we spoke privately, Burton made me feel very welcome. “Bernie, unlike most White people we work with, I hear that you are a lot like us. I know that you live in a quiet Tennessee valley and love nature very much, that you love dogs which makes you a Dog Man too and that at least some of your plumbing, like ours, is outdoors.” That was true because even though it was the late 1990s, my Tennessee farm still had only a well-built outhouse privy uphill from my cabin as my “throne”. From the beginning, we had lots to laugh about and many things for which we shared a reverence. Burton really made me feel trusted and at home.

Burton made sure to invite me to all Tribal Council meetings and to ask me to update the Council on whatever we were up to at the time. When I wrote a grant to fund the detox center and it was funded, I asked Burton to come offer prayers on the day that the renovation of a Riverton city garage into the detox center was initiated, along with an Eastern Shoshone spiritual leader and two Riverton Anglo ministers. That event was well covered by the local press that published over 200 front page articles on our activities in the four years I worked there in a host of capacities.

So I was very pleased when Burton invited me to accompany Tribal leaders to a national conference in DC on substance abuse in Indian Country sponsored by the US Department of Justice (DOJ). Of the 600 attendees at that conference, I was one of only four non-DOJ Anglos in the room. At lunch the first day, I was sitting across from Burton at a large table when an Eskimo leader pulled at Burton’s shirt, motioned to me and asked quietly (though loud enough for me to hear): “Who’s the White guy?” Burton smiled, briefly explained my role and then ended with “Bernie’s home is Wind River Country. He just doesn’t know it yet”.

That was not the last time Burton asked me to saddle up and ride with the Tribe. The Northern Arapaho were invited to give a presentation to the state’s Substance Abuse and Violent Crime Advisory Board, a Board that had no Indian people as members. I had met with that Board many times before that meeting and had gotten tired of the times that a few Board members had freely expressed their prejudices toward Indian people to me, implying or outright stating what an impossible task I had accepted since “all Indians are drunk Indians.” That day, in the presence of the Indian leaders led by Burton, I was able to present the conclusions of one of my many Wind River Country studies, an analysis of the ethnic makeup of county arrestees for substance abuse-related crimes. That study revealed that for every category of the number of arrests (only 1, 2-4, 5-9, 10+), the number of White arrests outnumbered the arrests of Indian people except for the highest arrest category (10 or more) where Indian arrests outnumbered White arrests.

But in that category, only twenty Indians accounted for over 60% of all arrests of Indian people (out of over 4,000 Indians in the county), demonstrating the need for detox services for these and other chronic alcoholics who were most visible and who contributed most to the “drunken Indian” stereotype. I ended my presentation by saying “I hope this dispels some of the misconceptions I have been exposed to in this Equality State since I first began working here. Frankly, as a seventh generation White Mississippian, it distresses me to have to come all the way to Wyoming to be reminded what racism sounds like out loud.” That comment was met with stony silence by some Board members and a chorus of A’hos (“Truth”) by the Indian leaders.

I have another strong memory of Burton and the thanks he gave me for the work I did for his people. By 2000, I had been working in Wind River Country for four years. In addition to our research work and the linkages I had forged between Gallup and Wind River leaders, I had written another grant to bring several $million$ in additional federal dollars to Wind River Country to establish the first detox center anywhere in the state. The grant was awarded to the City of Riverton who assigned the responsibility for establishing and running the detox center to the Fremont County mental health agency. That agency's director had siphoned off funds to increase his salary for over a year without doing any meaningful work to get the detox center off the ground. When the Feds became impatient over the inaction, that director's "solution" was to offer to return the unspent portion of the grant to the Feds without informing either the city, county or Tribes of that action. Needless to say, that stupid decision had both Wind River Country Indians and Cowboys on the warpath. The City of Riverton promptly jerked the grant from the mental health program.

Shortly thereafter, I was summoned to a meeting with the Riverton mayor, other city and county leaders and leaders from both the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes where I was informed of their dire situation. At that meeting, I was asked whether my company would be willing to assume complete responsibility for establishing and running the detox. Although my company had never attempted anything like that before, I told the assembled leaders that we would accept the challenge under two conditions. The first was that we be allowed to work ourselves out of the job within a year by hiring staff and assembling a local board of directors who could take charge of the center. The second was that they had to agree to pay my consultant fees for my own personal involvement in this effort upfront.

By then, all those leaders knew that my consulting fee ranged from $400 to $1,000 per day plus expenses so I was met with silence as the assembled leaders huddled and did the daunting math. After giving them a minute, I turned to the Riverton mayor and asked him if, by chance, he had a Sacajawea dollar in his pocket. (Sacajawea had been an Eastern Shoshone and was buried on the rez.) When he said yes, I asked him to give it to me. Then I said, "OK, I'm paid in full. Now let's get to work." After that meeting, Burton hung back and motioned me over to him. He said through his great and gentle smile: “All of us have been praying that you would take on this big task and that we could afford for you to do that. Thank you for answering our prayers. Evidently, for our people, you are both cheap and you can be had. A’ho!”

Within three months, we had the center built, the staff hired and had begun to accept patients. Every day, Burton joined us for lunch so that he could speak with Northern Arapaho and other clients, regardless of how far down their alcoholism had taken them, to let them know that the Northern Arapaho had not abandoned them, that they would always remain family. Within six months, we had accepted patients from a majority of Wyoming counties. Within a year, we had accepted patients from all Wyoming counties and we had also accepted patients from 14 other states who could not find detox services and treatment referrals at home.

Now, twenty four years later, that center (the Fremont County Alcohol Crisis Center) remains in place, having served thousands of people regardless of their ability to pay. And that Sacajawea dollar remains on my bookshelf in the same jar where I keep my AA anniversary chips (thirty years worth, so far). If there's anything I've learned in the intervening years of my federal prosecution-induced poverty, fear and loathing, it is that life is about so much more than money. Occasionally, though, money does reflect the measure of a man. And for what it's worth (and to me, it's worth a lot), I am happier to have earned that dollar than any other.

Little Joe Duran “With all things and in all things, we are relatives.”

Little Joe Duran was a mighty, mighty prayer warrior though he stood barely four feet tall. He was considered the Northern Arapaho’s principal medicine man and he could present himself with all the stature and ceremony that his title embraced. But like all of the other Northern Arapaho leaders, Little Joe warmed up to me very fast. If Paul Joe was my valued co-worker and Burton was a kind and loving counselor and uncle, Little Joe was my fun-loving friend, always joking around to make me feel at ease until I knew my place was a welcomed one in their midst with him showing me the way.

His welcoming ways went so far as to invite me regularly to sweat lodges where there were only Tribal elders and I was the only White person. At one very memorable sweat, there were two elders from the Crow Tribe who joined us. The sweat routine was to first smudge ourselves and the sweat lodge with sage and cedar to start the cleansing before we entered the sweat lodge. Then we did three rounds of sweat broken up by breaks where we stepped outside and cooled off for a few minutes. The first round of that sweat was pretty intense and when we took our first break, the Crow elders commented on how hot the first round had been. Then the second round came and I literally thought I would melt into a pink puddle on the sweat lodge floor. The heat was so intense that it took all I had to remain in a prayerful state though some of those prayers were that we’d get to the second break — fast.

When that break finally came, the Crow elders said that they were happy to have lived through those two rounds but they were not going to risk the third. That left just me and the Northern Arapaho elders. As we got ready to re-enter the sweat lodge, Little Joe walked over to me and asked me to lead the prayers for the third round. I didn’t know what to say and I told Little Joe that. His response? “Just say what is in your heart, your hopes and dreams for your people and ours and you will do fine.” That instruction made the third round, as hot as the first two, go smoothly with my mind focused where it should have been all along – asking for blessings for the People.

The next year, I spent a late August birthday at Wind River attending the Northern Arapaho Sundance ceremony which concluded a week-long Tribal homecoming and the initiation of young Northern Arapaho men into adulthood. All week long, the young men slept together in an enormous open air hogan with their heads facing outward touching the hogan walls while their women slept outside facing inward, with their heads also touching the hogan at the same spot as their partners. It was a really impressive display of tradition, respect, love and loyalty.

At sunset on the last night of the Sun Dance, Little Joe met me on the outskirts of the large crowd and took me away from the other Anglo visitors who were hanging on the periphery. He led me through the Tribe until we were standing beside a grandmother next to a large drum around which fifteen men sat ready to play. In the dimming magic hour dusk, the drum circle started and a chorus of maybe fifty Arapaho women near where Little Joe had guided me started ululating and chanting, bringing the entire crowd to their feet where we swayed and danced to the holy sounds. Just as the sun's last rays glowed behind the Wind River mountain range and a cool breeze started moving among us, a cloud formed overhead that caught my eye.

The cloud was shaped and colored exactly like a galloping paint pony and it glided slowly, very slowly, toward the sunset over all of us gathered for the ceremony. I just stood there, gobsmacked, transfixed by the beauty of that sky-horse, by the cool enveloping breeze, the sage and the cedar, the sights and the sounds. After a long while staring at that celestial horse, I looked down and my glistening eyes met those of the Northern Arapaho grandmother beside me. She pointed to me and then, silently, pointed to the sky pony. And then she beamed and nodded and said to me: “Little Joe is right. You belong here among us. Wind River is your home.” And then she smiled deeply once again, her own eyes glistening. And so did I, and so were mine.

My last blessing from Little Joe came several years later after the feds had raided my Tennessee farm and charged me with growing cannabis for myself to deal with degenerative joint disease and for dying AIDS and cancer patients. That raid and the subsequent federal charges I was facing brought the risk of my having to serve ten to forty years in prison, pay a $2 million fine and surrender my 187 acre Tennessee farm, all for the crime of easing my suffering and that of very sick people for free and for smoothing their transition to the Spirit world. The constant fear of those potential punishments hung heavy on me and I had basically shut down, spending day after day on my farm with persistent thoughts of suicide or of making my escape to Canada to avoid a long prison sentence that I sincerely believed I would be unlikely to survive.

It was then that I got a phone call from Little Joe one day out of the blue. I was surprised by the call and after a few pleasantries, Little Joe got right to the point: “Bernie, we have heard what has happened to you and all our people are really worried for you. Yesterday our elders met to decide what we might do to help you. They have asked me to call and make an offer to you – to hide you on our rez for the rest of your life. Don’t run to Canada. Don’t harm yourself. Come live with us. As you know, the Wind River rez has millions of acres and we have a cabin for you to use that is high on the side of one of our mountains. There is only one way in and one way out and you’ll be able to see anyone coming for at least twenty miles. And our Tribal police chief will call you to warn you if anyone who means you harm is heading your way.”

I sat there in my isolated Tennessee cabin listening to this miraculous offer and the tears burst forth, rolling down my face and soaking my tee shirt. When Little Joe finished, we both sat quiet for a minute to let my sobs subside. When I could finally catch my breath and slow my tears, I said to Little Joe: “My good friend, I have never been so touched in my life. You and your people have honored me more than anything else in my life by this offer. The thought of living on your beautiful land, surrounded by your beautiful and handsome people, really is appealing. But as much as I want to, I just can’t accept your offer. It would mean that I would have to spend the rest of my life looking over my shoulder. I will take this kind offer to my grave, thanking the Creator every day for it, but I just have to say no. I hope you understand.”

To which Little Joe responded: “Yes, Bernie, we understand. In fact, most of us know you well enough by now to expect that this is what you would say. But we had to make the offer anyway. It is always open to you if you change your mind. Wind River IS your home and wherever you go, it always will be here for you. As will we.”

Stanford Addison “If a man is to do something more than human, he must have more than human powers.”

That call from Little Joe was such a blessing that it buoyed my heart and calmed my fears quite a bit. I spent my days while awaiting my fate focusing on the peace and quiet of my deep holler home, the green of my land, the blue of my sliver of sky, the cool of my spring waters, the prayerful heat of my wood-fired sauna, the coos of mourning doves and the evening songs of tree frogs. It was in that constant state of living every moment in an attitude of gratitude that I received another call from Little Joe, this time very early in the morning. And this time, the message Little Joe brought me was from another powerful prayer warrior for the people, Stanford Addison.

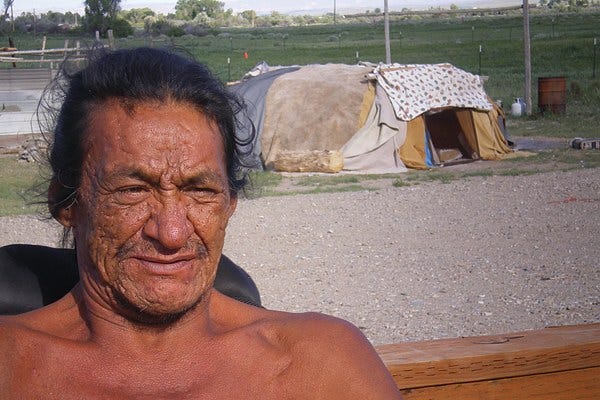

Although I had never met Stanford, I had heard a great deal about him. Stanford was a quadriplegic, having lost the use of his limbs in a tragic traffic crash on the rez years earlier. As he recovered from that crash, Stanford’s spirit grew and with it his well-revered and widely recognized spiritual powers. Stanford now made his living breaking wild horses from his wheelchair, allowing his spirit to welcome and calm those horses, to trust him and their new station that was to be of service to the Northern Arapaho people. Stanford always had help from young Northern Arapahos with the many steps that were necessary to introduce those horses to the bridle and the loving and gentle touch of Indian people. But it was Stanford’s voice and his spirit that touched and gentled them first and prepared them for everything that was to come, a future built on Stanford’s caring and caressing grace.

Stanford could not only do that with wild horses but he could do it with troubled men and women and with tense and fractured Indian communities. He was in constant demand to travel to reservations throughout the country that were beset with a host of serious and seemingly insurmountable problems. With his gentle and intuitive ways, his Spirit’s touch, his ear attuned to those people in pain and his voice channeling the counsel of the Universe, Stanford worked miracles. And he was revered everywhere because of it. In fact, his presence and his peace were so powerful that an excellent book was written about him and about his life and influence on the rez. I strongly recommend that book to you. It is entitled “Broken” and would be well worth your time to learn about Stanford, his people, wild horses and the Spirit.

On a very early morning, Little Joe called again and rousted me out of bed just before dawn. He explained that the People had just held a weekend long peyote prayer ceremony on the rez with Stanford leading the ceremony and the prayers. “Bernie,” Little Joe said “I’ve got some good news for you. We’ve just completed the ceremony. Throughout the weekend, hundreds of our People have prayed for you and for others like you in our Tribe who are facing uncertainty and distress. The power of those prayers was palpable to all of us and Stanford kept us praying together all weekend and of one mind. He just called me over to him not ten minutes ago and told me to call you right away and tell you to stop worrying …. that you are not going to prison.” It was as if a two ton weight had been lifted from my shoulders with those words and with mine, I thanked Little Joe, thanked Stanford and thanked all of their People.

Little Joe and I celebrated for a minute, laughing and reminiscing about all we had done together and all the life we had to be grateful for. I thanked him again for their powerful peyote prayers and Little Joe said: “Bernie, you must know that we’ve been praying for you everywhere this past year, in our churches and in every sweat lodge and prayer ceremony we’ve held. We owe you so much.” To which I responded: “Little Joe, you don’t owe me anything. You’ve blessed me for the past five years just to be invited into your presence and your confidence. And believe me, I not only know that you’ve been praying for me but I have known every time that you’ve prayed for me.”

Little Joe said: “How could you possibly know when we’ve prayed for you?” to which I answered: “Every time you’ve mentioned my name in your prayer ceremonies, I’ve smelled the sage and cedar on the western wind. From 1,800 miles away.”

Little Joe was quiet for a minute and then he chuckled softly and said: “Bernie, you know you’ll always have a home with us, on our land and in our hearts. And just so you know, you just think you’re White. We know better.”

Six months later, standing before my federal judge, I heard him say to me: “Bernie, you’re not going to prison.”

——-

Postscript: Sitting here this afternoon at my Ranchito Feliz Destino, on the high slopes of La Jicarita’s Hidden Valley in Taos County, NM, Stanford and Little Joe and Burton and Paul Joe have all blessed me again. They have all gone on to the next world where their Spirits were welcomed and their powers enhanced. Just spending the past few hours thinking of them and the purposeful, productive and prayerful work we performed together for their People has been another blessing, calming me and centering me for the challenges of today, refocusing me on what’s really important. I’m glad you’re all here to read these words of praise and admiration for my Northern Arapaho co-workers, counselors, supporters, prayer warriors and friends. They bless me still and they always will. A’ho.

This touches me deeply.

You are an incredible blessing to these people and many more